How Lena Rozvadovska fights for children. Story 2: Dima who survived bombardment

Lena Rozvadovska has been living in Slovyansk for a little over two years. She travels to the frontline and talks to the children. She calls herself a volunteer, because she has to call herself something.

At the end of 2014, Lena still lived in Kyiv and worked as a spokesperson for the Ukrainian President's Ombudsman for Children's Rights.

In early 2015, she left her job, packed up her things, took her off-season clothes and books to her relatives, sold the rest and moved to Slovyansk. Only for a short time, it seemed then, just a month or two, until the end of the war.

"You see," Lena explains why it was necessary to do so, "in 10 years we will have a generation of Ukrainians who have grown up during war and whom no one will understand."

She wants to understand, and she has many children here. In Avdiyivka, Zolote, Zaytsevo and Krasnohorivka. And the place I was with her.

[L]We go to Zaytseve. Because today is Saturday. For half a year Lena has been traveling to Zaitseve every Saturday to play with children.

Zaytseve has a bad reception of Ukrainian radio. There is no Ukrainian TV. Zaytseve doesn't even have electricity... The front line has divided the village - the school, the church and the village council remained "on the other side", just like Horlivka, the city where everyone used to go to work, to the market, to the hospital and to rest.

They shoot here mercilessly.

...Every Saturday Lena plays with the children in this building which houses a store, humanitarian headquarters, the church, the police and the village administration. It's also a mobile phone charging point.

Together we count how many children are left in Zaytseve: Dima, who was under fire. Edik, who practically never left even in times of heavy bombardment, he recently had a little sister born. Vikusya, or Vika. She takes you by the hand and shows you all of her toys at once. The boy Zhenya and little Camilla arrive only on weekends, Zhenya is very scared of shelling. Camilla is afraid to let go of her mother's hand.

There's also Adelina, who is 19 years old and who is formally no longer a child, and Diana, whom I did not meet.

"They all seem like ordinary children, but each one has a trauma from the war," says Lena.

We listen to the radio, the signal is constantly disappearing. Lena says:

- I traveled to Zaytseve on May 9, listening to "Halychyna" radio station. Near Mayorsk "Radio Victory" suddenly switched on. Imagine this, I am forced to listen to Plotnitsky: "The Euromaidan madness, we are fighting to preserve our language, culture, nation, we are Russians, we have won, we will be victorious..." A parade in the LPR... It was like hello from Mars!

"Hellos from Mars" are commonplace here.

...When we were in Avdiyivka, the "FM Army" signal disappeared immediately after the Nine (a shot up 9-storey building on Avdiyivka's outskirts - LH), at the entrance to Stara Avdiyivka. At this frequency it was replaced by "Radio Republic" promoting a concert of an Abkhazian dance ensemble. And this festive advertisement sounded like a mockery of this small Ukrainian city, which doesn't even have a cinema, not to mention a theater and circus. In order to attend a theater or a circus before the war they traveled to Donetsk. IT tokk them 20 minutes by bus. For the past three years, the only theater here is the war theater.

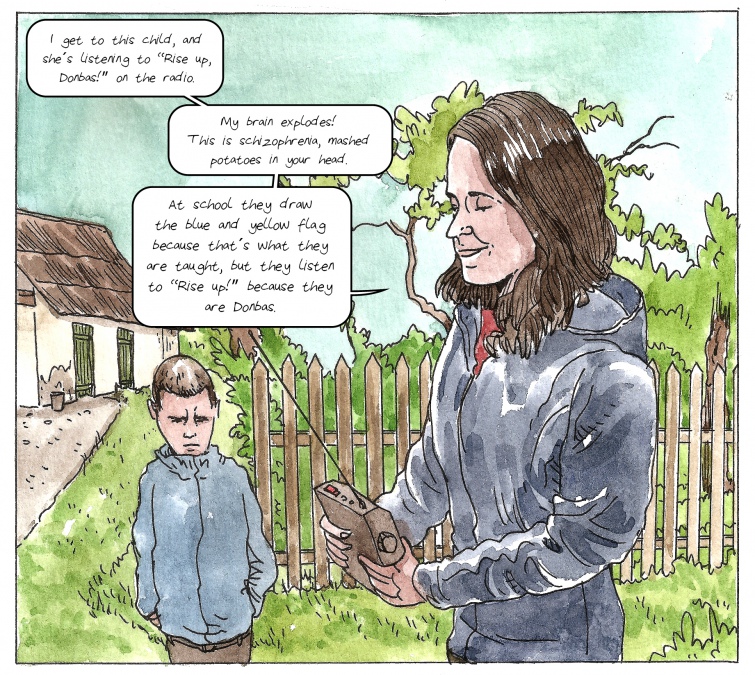

- I arrive to this child, and she's listening to "Rise up, Donbas!" on the radio, - says Lena. - My brain explodes! This is schizophrenia, mashed potatoes in your head. At school they draw blue-and-yellow flags because that's how they are taught, but they listen to "Rise up, Donbas!" because they are Donbas... They can even sing the soldiers the national anthem for UAH 10. I've heard of such stories...

|

| © Dan Archer |

- Do you talk to them about Ukraine?

- I don't talk to the children about patriotism, or Ukraine, because they should first restore faith in normal adults. You have to take into account the whole schizophrenia in which they live. An injured psyche will not accept any force. And in general, a child should simply have a childhood. But I never avoid the military and Ukrainian attributes, on the contrary. When it's possible, I always introduce the children to the soldiers. Often, it is the military who help us get to one place or another. International humanitarian mandate missions are always neutral in armed conflict zones, and even the presence of a Ukrainian flag can be seen as propaganda. That is definitely not about me. Just like those moans "we are for no one but for the people", "we are for peace", "both sides are bad" are not about me.

So, we're going to Zaytseve, to the children. To play. Yesterday there was an attack, but today is Saturday, and Lena has almost never missed a Saturday.

...Lena speaks on the phone with Volodymyr Vesyolkin, the head of the Zayseve MCA. She promises to call in and says that the village will receive about 400 liters of gasoline.

She explains: it's for Zaytseve, the gasoline is for the generators. She asks to divide it up for Bakhmutka, Zhovanka, Pisky (parts of Zaytseve that have remained under our control - LH) to distribute through volunteer points, where people come to charge their mobile phones.

The gasoline money was allocated by the "Pope for Ukraine" fund. Lena is their consultant. She looks for better ways to spend the Pope's money. But not on buckwheat. Gasoline for generators is her idea. Because everyone needs power and gasoline is expensive.

We talk a lot about humanitarian aid and what right and wrong humanitarian aid is.

Lena explains to me the standard scheme of humanitarian aid distribution. There are so-called categories. They include families with many children, people with disabilities, children under care, orphans, lone mothers...

- This is a standard list that every social agency has and this is the list which all humanitarian organizations request, - Lena explains the mechanism which allows for some families to receive food packages from all funds operating in the ATO zone. They are overwhelmed, they get picky about which kind of pasta they want.

On the other hand, a family with a mom and dad, one child or two children, where parents lost their jobs or a child got sick, won't receive anything. Just like a person of pre-retirement age who worked at a company which has been shut down. Such people, although they are not from any category, may be in a more difficult situation than those within the "categories".

Lena consults the "Pope for Ukraine" campaign: she searches for those who are really in need, not those who fit into some category.

We turn to Zaytseve and pick up Adelina first. Adelina's mother lives in Horlivka with her younger brother. Adelina lives with her grandmother, in Pisky. She visits her mom by crossing the collision line.

Adelina studied at a vocational school, which was left "on the other side". She quit her studies and attends hairdresser lessons, but Vesyolkin wants her to become a passport clerk. And Adelina, apparently, will agree.

She is already the chief humanitarian aid distributor in Pisky.

- When I met the cows today, everyone flocked to me. They said that Zhovanka had just received "hygiene", and no one came to us... - Adelina explains Pisky's "humanitarian" problem (the Pisky that is part of Zaytseve, not the airport).

The battle for humanitarian aid is a separate war during war, and Adelina ended up on the frontline of both of these wars.

We turn to Mayorsk. There we have to meet Vesyolkin, at the red shop. This is a place where flower pots are made of shell cases.

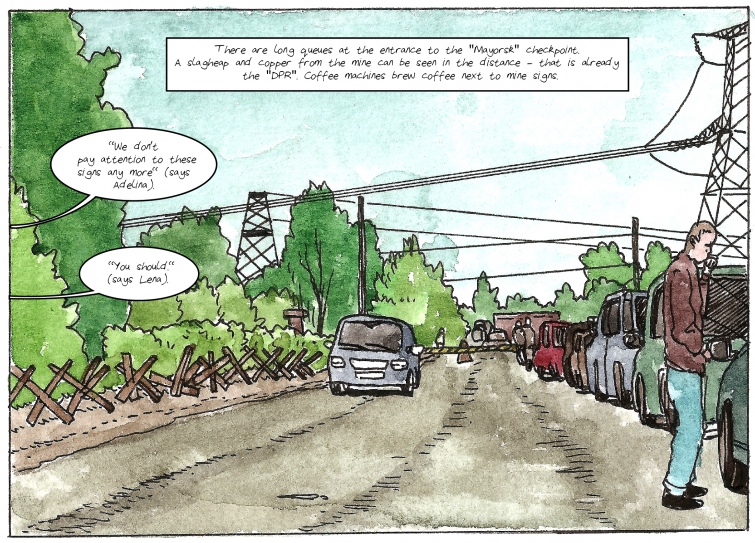

There are long queues at the entrance to the "Mayorsk" checkpoint. A slagheap and copper from the mine can be seen in the distance - that is already the "DPR". Coffee machines brew coffee next to mine signs.

|

| © Dan Archer |

- We don't pay attention to these signs any more, - says Adelina.

- You should, - says Lena.

She adds: I showed Lesya your drawings today... Adelina blushes, but she is pleased. Not because Lena showed them to me, but because she keeps them.

Women recognize Lena at the store.

- Why do you only work with children in Zaytseve and never work with our kids? - they ask.

They also say: our children are the same, they need it, too.

- What do they need? - asks Lena. She is embarrassed.

- The same that the Zaytseve kids get, - the women say. - When will you come to our children?

In Mayorsk, Vesyolkin offers Lena a room in a former kindergarten to play with the children.

We leave and think on the way: what's better - an old house in Bakhmutka (part of Zaytseve), where you can work in a corner behind a curtain or a nice room in Mayorsk where you can bring children from Bakhmutka? But it's less than a kilometer from point zero and there's no bomb shelter...

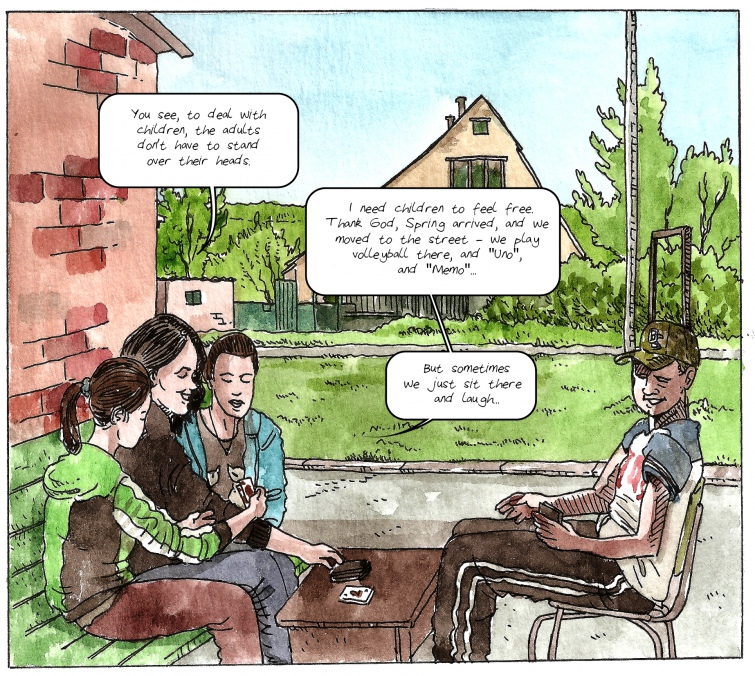

- You see, - says Lena. - To deal with children, the adults don't have to stand over their heads. I need children to feel free. Thank God, spring arrived, and we moved to the street - we play volleyball there, and "Uno", and "Memo"... But sometimes we just sit there and laugh ...

There are deep ditches on the dry road from Mayorsk, and Lena's car crawls to Zaytseve on its belly.

- You could go around on the grass. - I tell Lena.

- You can't drive on grass here... - she reminds me.

When it's quiet, I forget about it all the time. "About it" is about the war.

- It was all quiet as it is now, - says Victoria, Dima's mother. - So quiet that it was hard to believe. And suddenly it all started. The fields were burning, explosions everywhere... My husband threw me into the cellar, and I screamed: "Dimka?! Where's Dimka?!"

|

| © Dan Archer |

Victoria remembers how her son, Dima, then 13, was under fire, and her husband Valery went to look for him. It happened in the spring of 2015.

- It was a tank battle, - says Valera. - Separatists on one side, Ukraine on the other, and we were caught in the middle... Everything was flying over our heads. We jumped into the basement, but Dima wasn't there...

Then Valery says: I tied a white sheet to a hoe, raised it high above my head and went to look for my son.

I look at him and imagine a tank battle. And not far away, but right here. And I don't understand how it's possible to go out from a shelter under such fire.

With a hoe. Against tanks

- Take a picture of that hill. It's a real beauty, - says Valery. - Later show it to your friends and ask them where it is. They'll say it's in the Carpathians. You see the beauty of it? And this is our garden. We have goats and calves. This is Dima's goat...

Then, to feed the goats, Dima went to the river, and when the shelling began, he ran home. But he didn't make it. His father found him disorientated, covered in mud and grass. Dima couldn't understand where he had to go.

- I called him. Dima, Dima... But he didn't hear me... It took us an hour and a half to bring him to his senses. We rubbed him with water, gave him medicine... Then he recovered and asked, "Where was I?"

|

| © Dan Archer |

Victoria says he kept screaming every night... For several months. Later, it passed - after the camp, where he talked to a psychologist.

- After the camp, he became a different child - there are many children there, not like here. Here in Bakhmutka there are only small children, he has no peers here at all. And at school, he has a friend named Kolya. The teacher says they're inseparable, - mom says.

Last year, some Zaytseve and Mayorsk children went to school in Mykitivka. That part of Horlivka on the other side. Or they studied at home, remotely. Since the beginning of the school year, the Donetsk RMCA (regional military-civilian administration) has provided a bus to allow children to go to school in Bakhmut. But still some go to the "the other" side.

- Our children still stick together at school. They don't let anyone touch them. I know that he defended Masha. I asked him, "Dima, will the principal call me?" - "No". - "You fought?" - "No, I just came up and said: "You can't offend her", - Victoria says.

She says that Dima loves to go to school. Once, in winter, when there was a lot of snow, he cleared the whole street for the bus to pass... But the bus didn't arrive...

Once, an incendiary bomb fell here in the courtyard. This walnut tree saved the family: a shell struck it. If not for the tree, the shell would have hit the bedroom, where they all sat at the time.

- I closed up the window with bricks after that, - says Valery.

They have no electricity here, but parents power up the generator so that Dima can do his homework.

They also have a modem, but the signal is strong only behind the house, so Dima sits with his tablet in the garden...

The family lives off their land. They have a lot of livestock: 12 cows, also goats, chickens, a huge garden... Dima's goats, as the parents say.

- One time soldiers came to us, and the goat was giving birth. Dimka was helping her... And those guys were from the city and they asked to watch because they've never seen such a thing before.. Dima told them ok, you can watch. The goat gave birth to two little ones.

Victoria and Valery give us some eggs. They say: take them, take them, because we basically give them away.

- Soldiers sometimes offer money, but I tell them, "No need, just take them. And let there be piece", - says Valera.

- Want some sorrel? It's really good. And parsley. I've already handed out a bunch, - says Victoria. - You cut it and it grows back again. It's the same thing with parsley...

...We met Dima on his way back from school. He did not go to play with us: he needed to make a fence for the goats. They're his goats.

He's already in 8th grade, and after 9th grade he will go to Kostyantynivka to study for a veterinarian.

|

| © Dan Archer |

...That Saturday we played with Adelina, Vika and Edik. The game was called "Uno", I played it for the first time in my life, and everything was confusing.

- Lena, deal! - said Edik, who despite everything, didn't want to lose.

- Lena, don't fall sleep! - jumped Vika impatiently.

Two cats twisted under the feet - Separ and Ukrop. That's what the children called them, and somehow they distinguish between them. I couldn't even if I tried.

Later, Zhenya and little Kamilla came over. Zhenya has hearing problems and wears a hearing aid. He did not hear well before the war, and once during bombardment he was seriously stunned...

- He can't be here, his mother took him to Soledar, he studies there. He comes to visit just for the weekend, - explains Lena.

Little Camilla is three years old. In the winter she was still afraid of military uniforms, she was afraid to be left without her mother and she was afraid of all strangers in general.

[L]When the shooting started, Zhenya was immediately alarmed:

- Shots, shots, - said Zhenya, and didn't want to play anymore.

Camilla also didn't play. She just ran and sat down on Lena's lap.

Lesya Ganzha, text

Dan Archer, illustrations

Project undertaken with the financial support of the Government of Canada provided through the Global Affairs Canada.